“My vision is a world of accessible intuition.”

Biography

Viola spolin

November 7, 1906 to November 22, 1994

Viola Spolin was an actress, educator, director, author, and the creator of theater games, a system of actor training that uses games she devised to organically teach the formal rules of the theater. Her groundbreaking book Improvisation for the Theater transformed American theater and revolutionized the way acting is taught. Originally published in 1963 by Northwestern University Press, it remains an essential theater text. She developed her methods while working as a drama supervisor in Chicago for the WPA, at her Young Actors Company in Hollywood, and as Director of Workshops at The Second City. Her son, director Paul Sills, who is credited with popularizing her work, used her theater games when he co-founded Compass, Playwrights Theatre Club, The Second City, and created Story Theater. The modern improvisational theater movement is a direct outgrowth of Spolin’s methods, discoveries, and writings. Read more about her life and work below.

Learn more about Improvisation for the Theater, and Spolin’s other publications here.

Philosophy

Viola Spolin’s improvisational Theater Games are a complete system of actor training. Each game or exercise has a focus, a problem to be solved by the players as a group, so that lessons are learned through play (experience). She wrote: "Everyone can act. Everyone can improvise. Anyone who wishes to can play in the theater and learn to become stageworthy. We learn through experience and experiencing, and no one teaches anyone anything. . . . ‘Talent’ or ‘lack of talent’ has little to do with it.” Through focused attention, a player can be in the present time, their intuition activated and their whole body alert and ready to play—physical states that benefit theatrical communication and liberate the individual to explore their environment and make new discoveries. In moments of pure spontaneity, cultural and psychological conditioning fall away, allowing for the player to explore the unknown. In theater games, space objects replace props and sets, which opens the possibility for theatrical transformation. Spolin called transformation the heart of improvisation. She believed cultural and familial authorities often use approval and disapproval to control others, limiting the individual’s capacity for experience. Her evaluation methods instead involve the whole group in a non-judgmental process that lets students learn for themselves. Spolin called her teaching methods non-authoritarian, non-verbal, and non-psychological.

EARLY YEARS (1906 - 1925)

Born Viola Mills in Chicago in 1906 to Russian Jewish immigrants, Spolin was raised in a lively extended family who came together to sing, play parlor games, and mount plays they’d written and improvised. She later recalled that the children were allowed to play free of adult supervision for hours at a time, often creating their own dangerous and thrilling games at nearby construction sites or abandoned lots in their Humboldt Park neighborhood.

Spolin developed an interest in the theater, both through family theatricals and the productions her father would take her to see while he was on opera detail with the Chicago Police. In high school she played basketball and was a forward-thinking girl who sometimes dressed in men’s clothing, wore bright red lipstick, and bobbed her hair. She and her girlfriends took nicknames (she was known, appropriately enough, as “Spark”), shared an old Model T Ford truck, and generally created fun for themselves wherever they went.

STUDY WITH NEVA BOYD (1923 - 1926)

After high school, she joined her sister Pauline who was studying with Neva Boyd. Boyd was an early theorist of the educational and social benefits of play who trained social workers in group work. Miss Boyd’s curriculum included folk dancing, storytelling, arts and crafts, table games, and the playing of traditional children’s games that she had gathered from across The United States and Europe. Neva Boyd’s Handbook of Recreational Games remains an indispensible book for teachers.

Neva Boyd with Paul Sills, 1928

For three years starting in 1923, Spolin studied at Boyd’s Recreational Training School at Hull House, though the school would later be moved to Northwestern University where Boyd became a professor of sociology. Of Boyd’s training, Spolin wrote: “The effects of her inspiration never left me for a single day.”

Neva Boyd was involved in the progressive education movement that had flourished around settlement houses such as Jane Addams’ Hull House. Jane Addams was on the board of an earlier school Boyd ran to train playground supervisors and even visited her classroom to speak on the subject. Like Addams, Boyd believed in using the democratizing forces of education to help integrate immigrants into the existing culture. Boyd believed that this goal could also be achieved through non-competitive play. In Boyd’s essay “The Theory of Play,” she wrote: “Social living cannot be maintained on the basis of destructive ideologies – domination, hate, prejudice, greed and dishonesty. A society cannot hold together without a good way of life for all. . . . Virtues are dynamic products and cannot be taken over fully developed without being continuously developed.”

Games, Boyd knew, helped children learn language skills, socialization, cooperation, and even morality, because all must agree on the rules and abide by them for a game to be any fun. And the act of playing changes the participant. She wrote: “Play involves social values, as does no other behavior. The spirit of play develops social adaptability, ethics, mental and emotional control, and imagination.”

Spolin later told an interviewer: “The only person I felt was the inspirator of my life was Neva Boyd—and she continues to be.”

MARRIAGE, CHILDREN, AND THEATER TRAINING (1927 - 1935)

Her high school sweetheart was named Wilmer Silverberg. He was the brother of her best friend “Chick.” Wilmer and Viola married shortly after her high school graduation. Their son Paul was born in 1927, followed by William in 1929. Wilmer later changed his surname to Sills. Viola and Wilmer divorced in the early 1930s.

On an early resume, Spolin wrote that when she wasn’t able to work after Paul was born, she hosted her friends for informal improvisations and games at her home on Saturday nights. She told theater historian Jeffrey Sweet that they’d prop the baby on the bed to watch. She suggested that the roots of The Second City were in those weekly gatherings.

She acted in productions in the Chicago area and from 1931 through 1935 majored in dramatics at DePaul’s night school. In this period she studied with Charlotte Chorpenning at The Goodman Theater. She worked as a stage manager for a theater company and for an advertising show for Heinz that ran five times a day at the 1934 World’s Fair.

By the mid-1930s, she was able to put the group-work she’d learned with Miss Boyd to use leading recreational programs at orphanages, bible schools, and for “working girls.”

In 1935 she went to New York to study acting with The Group Theatre, leaving her young boys with family. She studied with Lewis Leverett and met Stella Adler, John Garfield, Morris Carnovsky, and other notable members of the company, but returned to Chicago because she missed her children.

THE EDUCATIONAL PLAYROOM (1934 -1937)

Halloween at The Educational Playroom

Spolin and a group of young divorced working mothers rented a lakeshore mansion on Sheridan Road to live and raise their children communally. They called the house The Educational Playroom. Paul Sills recalled that the rent was more affordable in the middle of The Great Depression because many wealthy people had lost their homes. The Educational Playroom was next to Oscar Mayer’s house, and Sills remembered seeing the large man leaving each day in a long overcoat and top hat. The mothers pooled their resources, hired a cook, and shared the responsibilities of child-rearing, so they could work knowing their children were in good hands. Paul Sills said that John Garfield and other notable members of the Group Theatre stopped by to visit when in Chicago.

WPA ERA (1937 - 1941)

By 1937 she was teaching folk dancing and creative dramatics for the WPA at a training camp for recreational instructors, at Hull House, and wherever they would send her for field visits. In a l937 letter to her sister Pauline, she wrote: “I am beginning to make a name for myself in creative dramatics. . . . Everyone made such a big fuss about the unusual results I got. I used the charades a good deal as a means to teach acting techniques, and I realize that I have learned an amazing lot in the last years—both by my training under competent people and my awareness of living and the necessity to help people become more creative as a real justification for living.”

Viola Spolin, 1930s

In 1939, Spolin become a drama supervisor for the WPA Recreational Project in Chicago after being recommended for the position by Neva Boyd. Through 1941, she worked with children and recent immigrants in low-income neighborhoods. She felt the need to establish a form of theater training that incorporated what she’d learned about the benefits of play from Neva Boyd, one that could reach across divisions of culture and language. Lectures about traditional theater techniques were useless with children or adults with limited English skills, but when those lessons became the focus of a game, the students were able to incorporate them organically, full of the spontaneous physical expression needed for true theatrical communication.

Spolin said: “The games emerged out of necessity. I didn’t sit at home and dream them up. When I had a problem (directing) I made up a game. Then another problem came up, I just made up a new game.”

Like her mentor Neva Boyd, she rented space at Hull House to run her workshops. Sometimes she actually had to go out into the streets and round up students. She’d find kids who were playing games and invite them to play inside on the stage. Eventually, they’d let her introduce theater games as well. Her son Paul Sills was one of her students at Hull House. See Sills being directed by Spolin in the first photo below (center, holding script).

Some of the first modern improvisational theater performances emerged from these groups, with players taking suggestions from the audience to create scene improvisations and plays.

Chicago Daily News writer Howard Vincent O’Brien wrote of a 1939 production at Hull House that Spolin directed called Halsted Street: “People’s Play: Few will ever see this play, and I doubt if any professional critic will ever hear of it. Yet for importance I think it is worth about a dozen Broadway successes rolled into one. . . . There were about 150 people in the cast—Italians, Greeks, Mexicans, Negroes. . . . They were all ages and both sexes. What they were doing is not exactly a play. It was perhaps what is called a revue. But its form doesn’t matter. The important thing about it was that it was conceived, written and played by the people themselves.”

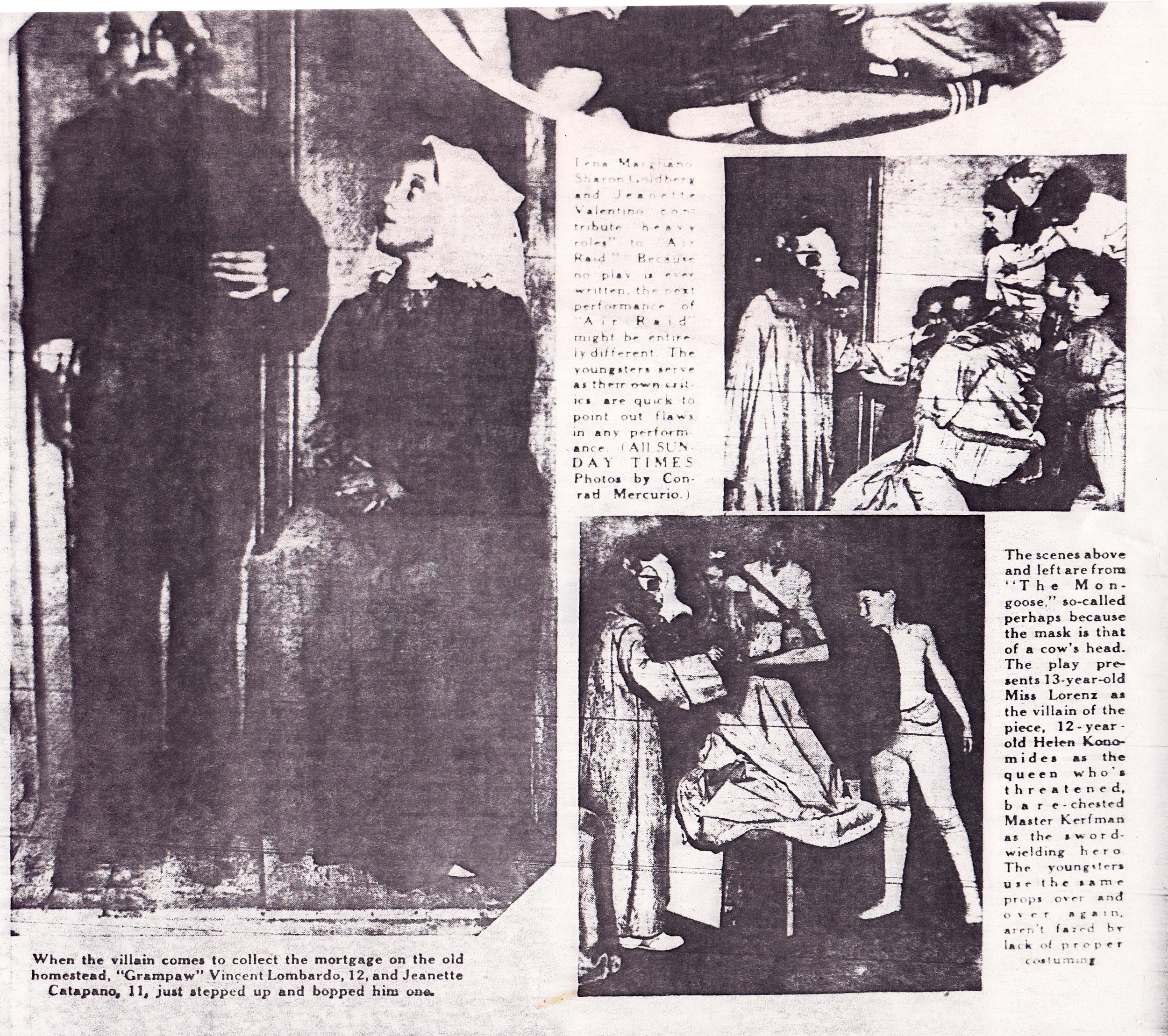

In 1940, the Sunday Times Magazine reviewed a children’s performance and wrote: “Organized recreation for children takes many unique forms, none more unique than what is being done at Hull House. Aimed at stirring creative ability inherent in all children, it’s a program of unorthodox drama that hews to no lines, knows no cues, and never heard of a rehearsal. The youngsters are given a bare idea, characters are chosen and the impromptu play begins. It’s fun, stimulates reading, eliminates the ‘dis, dat and dose’ from the children’s speech. Are these young thespians good? They’re the finest ad-libbers the stage has seen, says Director Viola Sills Spolin.”

THE WAR YEARS & THE YOUNG ACTORS COMPANY (1942 - 1954)

She fell in love and married a dashing builder and theater carpenter named Ed Spolin in 1940. During the Second World War, Ed was stationed on a Red Cross ship in the Aleutian Islands. Viola and her two teenage sons moved to San Francisco where she worked as a “Rosie the Riveter” in a shipyard and conducted theater workshops.

After the war, she and Ed moved to Los Angeles. Together they built a house in the Hollywood Hills. In 1947 Ed worked as a carpenter for renowned architect Rudolph Schindler.

Viola Spolin, 1946

She established the Young Actors Company in Hollywood in 1948, which was both an acting school for children and a professional repertory theater. Her student actors were steeped in her unique non-authoritarian and non-verbal teaching methods. All the while, she continued to create and develop her theater games.

Located next to the Hollywood Women’s Club on La Brea north of Hollywood Boulevard, The Young Actor’s Company's elaborate productions directed by Spolin developed a devoted following. She attracted many students from ages five to nineteen. Among them were future Second City players Alan Arkin and Paul Sand (Sand would later win a Tony-award for Paul Sills’ Story Theatre), and Jackie Joseph, who became a television and film actress. The company filmed a segment for KTLA, which unfortunately was most likely not preserved.

During this period Spolin wrote occasional op-eds and articles about the effects of television on young minds and other educational issues.

When asked how she found so many talented young actors, she would reply that it was not a matter of talent—what they were seeing was children who were free.

PLAYWRIGHTS THEATRE CLUB & COMPASS (mid-1950s)

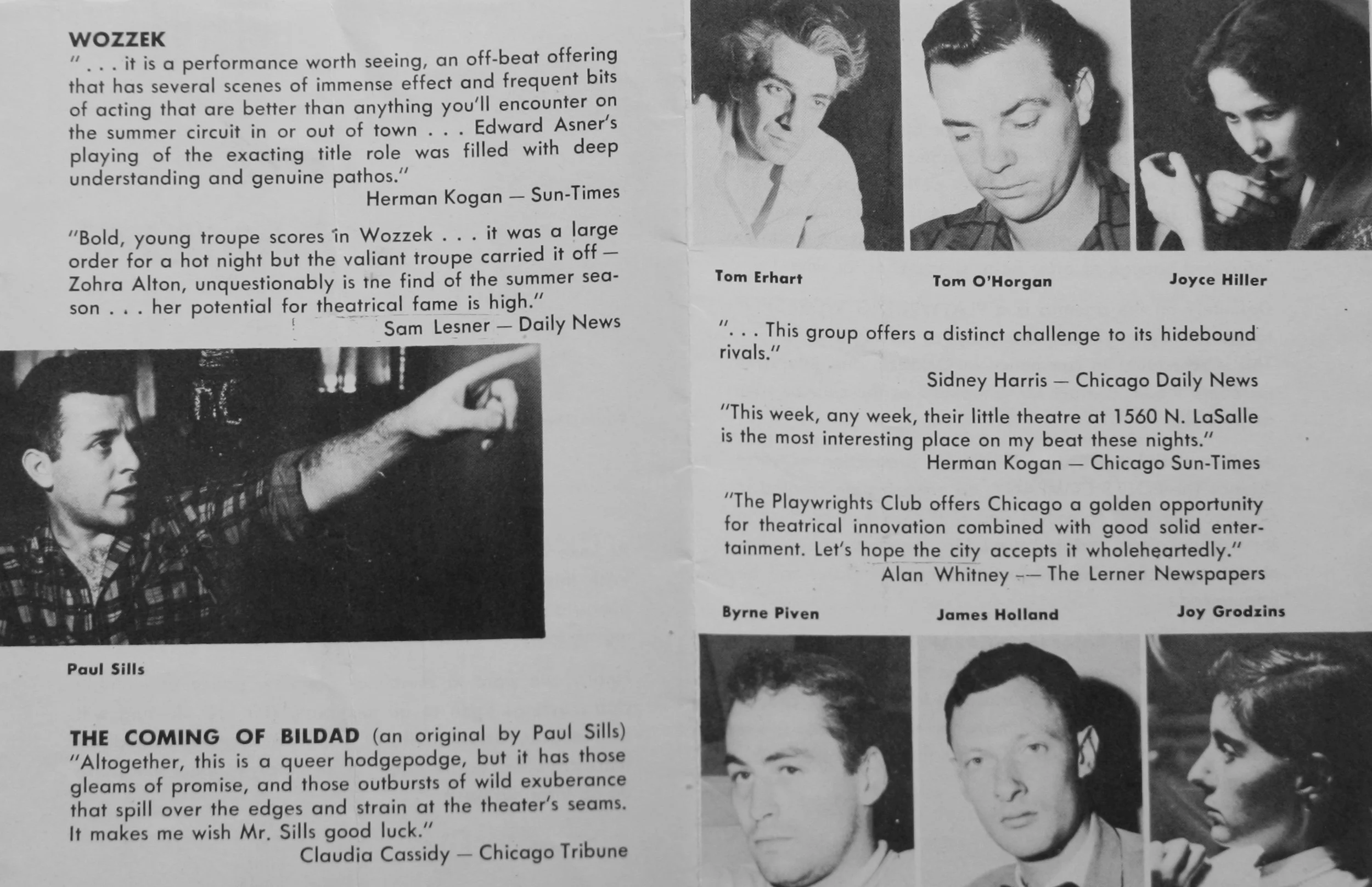

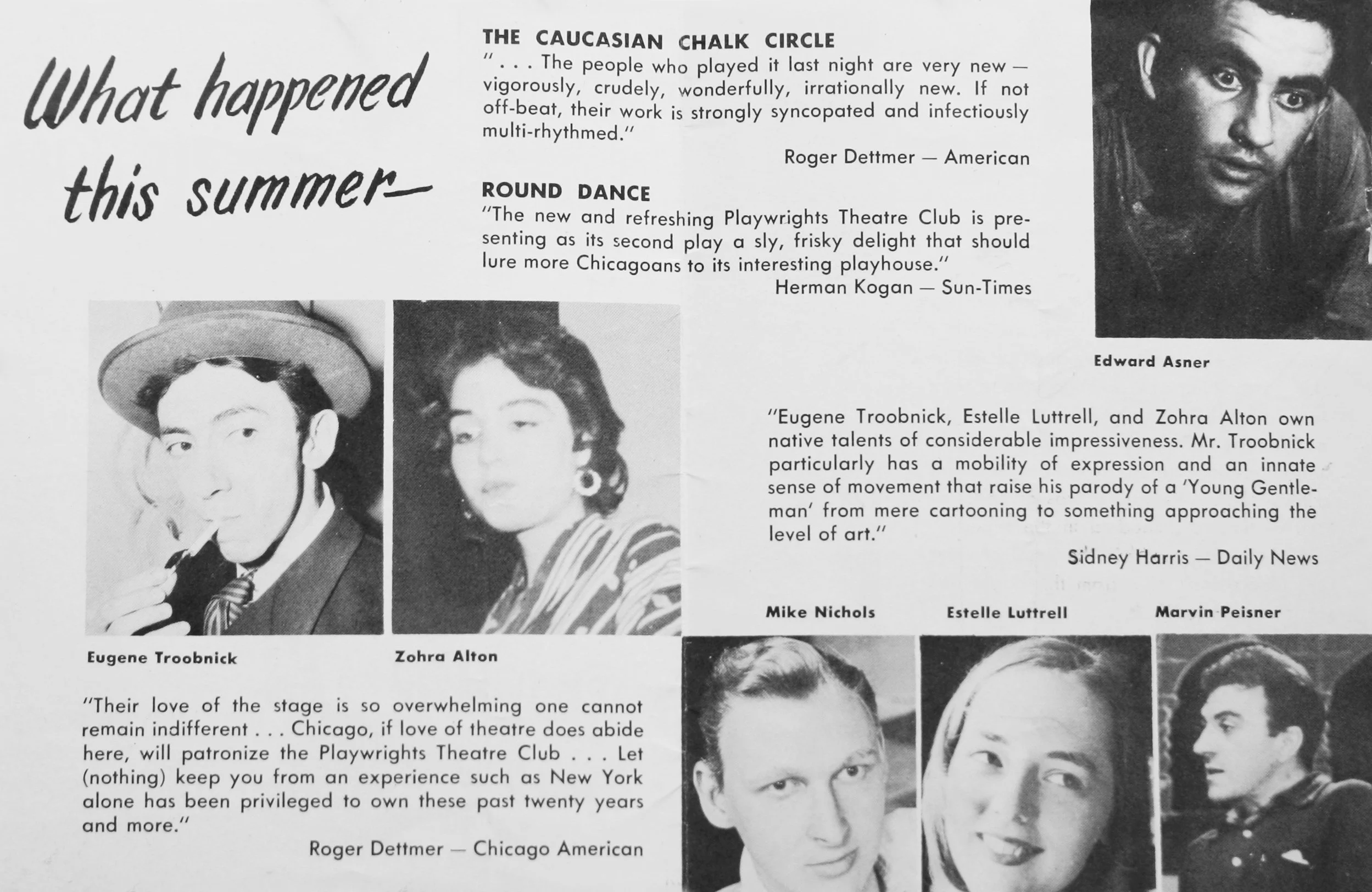

In the mid 1950s Paul Sills asked his mother to return to Chicago to direct Juno and The Paycock at Playwrights Theatre Club. Playwrights grew out of the dramatics club at the University of Chicago, where Sills attended. The University had no drama department so Sills and group of fellow students created their own theater. In the winter of 1952, he began running workshops in his mother’s theater games in hopes of building an ensemble. The company included Elaine May, Mike Nichols, Ed Asner, Barbara Harris, Joyce Piven, Eugene Troobnick, and Sheldon Patinkin. Playwrights opened in a converted Chinese restaurant in Hyde Park in 1953 with Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle, directed by Sills, and went on to produce many classic, new, and original plays. It is considered the beginning of the Chicago Off-Loop theater movement.

In 1955 Playwrights Producer David Shepherd and Paul Sills were forming a new improvisational revue-style theater called Compass. Shepherd invited Spolin to run workshops with the players (Nichols, May, Harris, as well as Roger Bowen, Andrew Duncan, and others). Members of the company wrote scenarios that the group would improvise from, and then improvise shorter scenes to round out the evening. Now widely viewed as the first modern improvisational theater, Compass’ innovations were in large part based on the teaching of Spolin.

THE SECOND CITY (1959 - 1965)

Sills opened The Second City in 1959 with friend Howard Alk and producer Bernie Sahlins. A smart satirical revue, The Second City was an immediate hit with audiences. The company developed their sketch material in workshop through improvisation, and closed the evening with a shorter improvised set. Again, Sills asked his mother to come to Chicago to run workshops to train the company in her methods. She once joked that a two-week visit turned into a seven-year stay.

By now separated from Ed Spolin, she settled into the Lincoln Hotel and became Director of Workshops at The Second City. She worked with cast members such as Richard Schaal, Avery Schreiber, Del Close, Mina Kolb, Hamilton Camp, and many others. Here she discovered and explored her innovative Transformation exercises. She also offered workshops to the public, including youth classes.

During this time, inspired by her work with the cast of The Second City, she began gathering her thoughts about her life’s work and started writing what would become Improvisation for the Theater.

IMPROVISATION FOR THE THEATER (1963)

In 1963, Improvisation for the Theater was published by Northwestern University Press. The theater and educational communities greeted Spolin’s theater games and groundbreaking teaching methods with excitement and enthusiasm. Countless improvisational theater troupes were founded across the country.

Film Quarterly said, “The exercises are artifices against artificiality, structures designed to almost fool spontaneity into being.”

Eric Bentley wrote: “Schiller taught us long ago that we are fully human when we are at play. Shakespeare has the phrase ‘all the men and women merely players.’ I like to think of Viola Spolin's theory and practice as beautifully exemplifying such truths.”

The book is now in its 3rd edition, updated to include the many theatrical discoveries she made after its initial publication.

GAME THEATER AND STORY THEATER (1965 - 1967)

Paul Sills felt the time had come to begin exploring the theatrical possibilities he’d found emergent in his mother’s work. He considered doing this at The Second City, but ultimately did not wish to change the successful format. He left to form the Game Theater with Spolin and members of the arts community who had been meeting to play Neva Boyd's traditional games in Lincoln Park. All were searching for new forms of creative engagement in the midst of the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. Spolin remained the Director of Workshops at The Second City until Sahlins and Patinkin asked her to leave once Sills had moved on.

Game Theater audience members were invited to join the company playing theater games in performance, a true expression of Spolin’s concept of the audience as fellow player. (See Roger Ebert and other audience members participating in a Space Walk, in the third photo below.) Spolin often led lively evenings of play, which allowed for further exploration of her work’s potential as a performance medium as well as a teaching system. The theater served as a hub for community groups such as the North Side Cooperative Ministry, Parents School, and Women for Peace.

Sills experimented with the staging of fairy tales at the Game Theater in 1967, which led to the creation of Story Theater, the theatrical form he would work in for the rest of his life. In 1970, Paul Sills’ Story Theatre enjoyed a successful run on Broadway, featuring Paul Sand, Valerie Harper, Richard Schaal, Richard Libertini, Melinda Dillon, Hamilton Camp, Peter Bonerz, and Mary Frann. Spolin consulted on many Story Theater productions in the 1970s. Her Theater Games for Story Theater was published in Paul Sills Story Theater: Four Shows (Applause Books).

Often overlooked in the discussion of Chicago theater history, the Game Theater represented a highly creative period for Spolin and Sills and was a community space that served the people of Chicago in important ways during a tumultuous time.

PUBLICATIONS AND WORKSHOPS (1970s and 80s)

Spolin returned to Los Angeles in 1966. In the 1970s and 80s she conducted many workshops at colleges and universities such as Sarah Lawrence, Brandeis, and USC, for education and theater conferences, for public school systems around the country, at the Esalen Institute, for the American Conservatory Theatre, Sills & Company, for drama therapy programs, in mental health facilities and for prisoners. She also ran workshops with the casts of television shows such as Rhoda and Friends and Lovers.

In 1970, she performed in the Paul Mazursky film Alex in Wonderland starring Donald Sutherland. Of note is a Felliniesque dream sequence in which she rode a white horse wearing a tutu. She’d earlier appeared in the independent film Goldstein (1964), which featured Nelson Algren, Del Close, Anthony Holland, and Severn Darden.

In 1975 she created The Spolin Center in Los Angeles, an acting school offering in-depth training in her methods.

That same year she released the Theater Game File after being plagiarized by authors who re-wrote her original material and put it out in an index-card form. Spolin sued the company, and her authorized version was published.

Sills & Co. in Los Angeles, mid 1980s. Left to right: John Brent, MacIntire Dixon, Valerie Harper, unknown, Peggy Pope, Richard Libertini, Viola Spolin, Severn Darden, Paul Sills, Lewis Arquette. Photo by Jan Butchofsky.

By the early 1980s Paul Sills had moved to Los Angeles and formed Sills & Co. as a cooperative with some of his longtime players. They built a theater in which to explore Spolin’s theater games in performance. The company consisted of veteran Second City and Story Theater players such as Severn Darden, Valerie Harper, Mina Kolb, Hamilton Camp, John Brent, Lewis Arquette, Richard Schaal, Garry Goodrow, Richard Libertini, and Avery Schreiber, who delighted audiences playing theater games such as Gibberish Interpreter, Animal Images, and Transformation of Relationship. Spolin conducted workshops for the cast throughout the company’s years in L.A. After Paul Sills and some members of the company moved the show to New York, Spolin took the reigns of the theater for a time and put on shows with a few of the remaining original players and members of her workshops, some of whom still perform together as The Spolin Players.

Theater Games for Rehearsal: A Director’s Handbook was published in 1985. It was recently updated in a new edition with a foreword by director Rob Reiner. Reiner has used Spolin games throughout his career, including before filming Stand By Me. In 2010 he wrote, “It was like a crash course in acting. After that, these relatively inexperienced actors who hadn’t known each other became a cohesive group. The result was four boys who seemed as though they had spent their lives together, and the film worked in large part because of that.”

Spolin went on the publish Theater Games for the Classroom in 1986, a guide to working with children in a school setting, which remains her best selling text.

Her last book, Theater Games for the Lone Actor was published posthumously. All of her books remain available from Northwestern University Press.

After suffering a stroke in the early 90s, Spolin was no longer able to teach. She lived out the rest of her days in her Hollywood Hills home with her devoted husband of many years, Kolmus Greene.

Since her death in 1994, Spolin’s legacy has exponentially grown. Through the booming improvisational theater movement, the continued use of theater games for actor training in schools and universities around the world, and the increasing awareness in the fields of education of the need for play and child-led teaching techniques, Spolin’s groundbreaking work continues to find new practitioners and exponents in a wide array of therapeutic applications. She lit a spark that changed the world.

No part of this Website, including text, graphics, sounds or images, may be reproduced or retransmitted in any way, or by any means, without the prior express written permission.